- Updated 2024.10.23 18:06

- All Articles

-

member

icon

-

facebook

cursor

-

twitter

cursor

| |

|

|

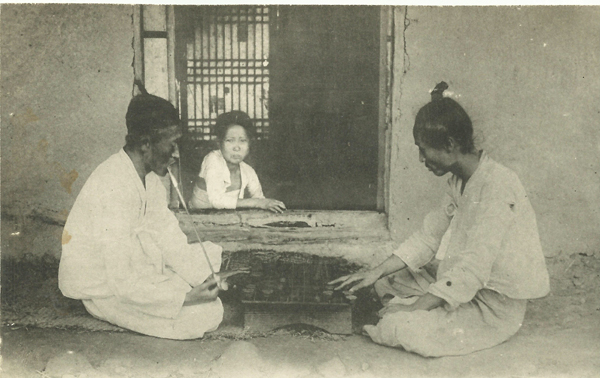

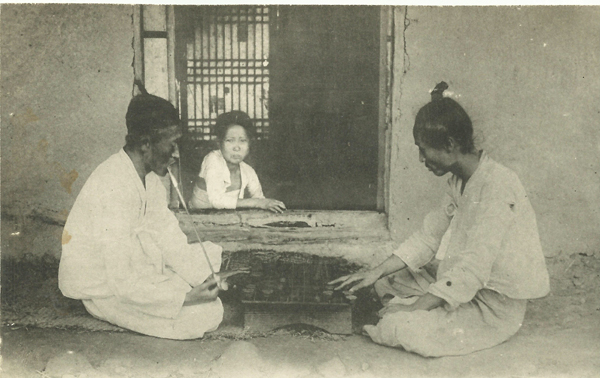

| ▲ Koreans at home circa 1905-1910. Courtesy Robert Neff Collection |

In some aspects the role of the Korean woman in the household was no different from the past as it is in the present. Korean women controlled the household and, in the cases where there was more than one wife or concubines, the first wife ruled. By extension, some women controlled the money or at least the enforcement of collecting debts.

A Westerner in the late 19th century noted that women were sometimes sent to collect overdue debts because of their sharp tongue and their dogged persistence. As if to confirm this, Arnold Henry Savage-Landor, a Canadian who visited Seoul in the winter of 1890/91, wrote about an incident he witnessed of a determined woman trying to collect an unpaid debt from a deadbeat soldier.

The dispute with the soldier occurred in front of the merchant’s residence. He, the merchant, demanded the money that was due him but the soldier dismissively replied that he did not have any money and tried to get away from the man’s angry tirade. Suddenly, from the doorway, came the merchant’s wife armed with a heavy wooden mallet commonly used for beating clothes and immediately put it into use by pounding the soldier over the head.

“The husband, encouraged by this unexpected reinforcement, boldly attacked the soldier, and, whilst they were occupied in wrestling and trying to knock each other down, the infuriated woman kept up a constant administration of blows, half at least of which, in her aimless hurry, were received by the companion of her life who whom she was fighting. Once she hit the poor man so hard — by mistake — that he fell down in a dead faint, upon which the soldier ran for his life, while she, jumping like a tiger at him, caught him by the throat, [spun] him round like a top, and floored him, knocking him down on the ice. Then she pounced on him, with her eyes out of her head with anger, and giving way to her towering passion, pounded him on the head with her heels while she was hitting him on the back with her mallet.”

Fortunately for the soldier, the blow that would have crushed his head was foiled by the woman’s slip on the ice. The moaning of her husband confirmed that he was still alive but the woman was still unwilling to let the soldier flee without taking her pound of flesh.

“The soldier, more dead than alive, had raised himself on his knees when that demon in female attire rose again and embracing him most tenderly, bit his cheek so hard as to draw a regular stream of blood.”

Unwilling to see the soldier suffer any further injuries, Savage-Landor foolishly decided to intervene and learned a most painful lesson. “Still manipulating [the mallet] with alarming dexterity” she struck him on the left knee leaving him seeing stars and vowing never to interfere in other people’s quarrels again.

With incidents like this, it comes as no surprise that some pawnshops in the countryside, and probably Seoul, were operated by women.

Operating pawnshops were “a very lucrative calling” but required a large amount of initial capital so not many people could actually establish one. According to one Western observer, “It is not regarded as at all a ‘low’ sort of business in Corea, and to engage in it entails no loss of caste” and that “women can engage in the trade without the same loss of caste as those women who sell wine.”

Speaking of selling wine, an upper-class woman in need of money could turn part of her home into a wine shop but, as one early writer noted, would never appear in person. The customers were served by a clerk or barmaid — the lady’s servant or slave. According to the writer, “No lady will ever sell cloth or vegetables or fruit or anything, in fact, except wine.”

However, most inns and drinking establishments were operated by men and those managed by women were not women of the upper social classes but rather those in the lower classes. But it is striking to note that in small villages, if we are to believe the accounts of the Western travelers, these women often tended to cow the reluctant males into performing their duties. It was customary in the past that when travelers entered a village at night and there were no rooms for them, the villagers would provide torches and torchbearers to escort travelers to another village. This was no easy task as tigers, leopards, and wolves haunted much of Korea and occasionally preyed upon travelers at night.

Some women also strayed from their roles as innkeepers and appear to have dabbled in early human trafficking. In September 1896, a woman in Chemulpo (modern Incheon) enticed a young girl from a village and kept her in a house of ill fame. The girl somehow managed to escape and reported the woman’s betrayal to the police who promptly arrested her.

|

How much were women paid?

Women were generally paid less than men but, according to one source, it was not because they were women but because they did not have “requisite strength or ability to do work equal to a man’s work.” Women in the southern provinces, as opposed to those in the northern provinces, enjoyed wages more comparable to their male counterparts.

Some of the highest paid workers were women acrobats who made about four dollars a day but probably only worked a couple of times a month and probably faced stiff competition as many of the itinerant circuses used boys dressed as women. Women fortunetellers also had a fairly lucrative occupation — especially if they were good — and generally made about eight cents per fortune, but these readings usually lasted about an hour or two. A wet-nurse made about 40 cents while a makeup artist for weddings made 10 to 16 dollars per wedding.

The best paying occupation for Korean women appears to have been that in the medical field. A physician generally earned a steady 10 to 40 dollars a month.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ⓒ Jeju Weekly 2009 (http://www.jejuweekly.net)

All materials on this site are protected under the Korean Copyright Law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published without the prior consent of Jeju Weekly. |

|

|

|

|

| Jeju-Asia's No.1 for Cruise |

|

|

|

Title:The jeju Weekly(제주위클리) | Mail to editor@jejuweekly.net | Phone: +82-64-724-7776 Fax: +82-64-724-7796

#503, 36-1, Seogwang-ro, Jeju-si, Jeju-do, Korea, 63148

Registration Number: Jeju, Ah01158(제주,아01158) | Date of Registration: November 10,2022 | Publisher&Editor : Hee Tak Ko | Youth policy: Hee Tak Ko

Copyright ⓒ 2009 All materials on this site are protected under the Korean Copyright Law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published

without the prior consent of jeju weekly.com.

|