| |

|

|

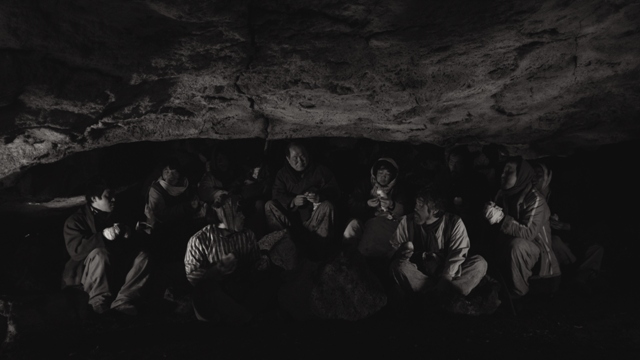

| ▲ O Muel’s Jiseul portrayed to an international audience ordinary people’s lives during the 4.3 Massacre. Photo Courtesy Japari Film |

Heo Jaegon and his wife Chun Eunsun were both 1 year old when the soldiers came to Jeju.

This tumultuous period in Jeju’s history is the subject of the film 'Jiseul' by Jeju filmmaker O Muel. Heo and Chun, both survivors of the massacre that overwhelmed the island from 1947 to 1954, introduced Jiseul to Jeju’s international community at a Dec 20 screening at The Factory in Jeju City. The film won the World Cinema Dramatic Grand Jury Prize at the 2013 Sundance Film Festival.

Following political tensions which erupted into violence on April 3, 1948, armed forces were deployed by the transitional government to suppress leftist insurgents on Jeju Island. The operation soon became a scorched-earth campaign in which any person more than 5 kilometers from the shore could be killed on sight. This period would later become known as the Jeju Uprising or 4.3 Massacre, and it would see the death of an estimated 30,000 Jeju villagers.

“When [Heo] was young he lived very high in the hills,” translator Yu Eunbin told the international audience. “The army came and asked his mother to cook them food.” The soldiers held Heo as his mother cooked. Heo’s father, a political dissenter, hid under the deck while his wife fed the soldiers.

Heo and Chun told of how the villagers helped each other through the dangerous times.

“[The villagers] made a signal for when the army cars came to find people,” they recall. “If the car came, they put a stick on the hill and they put it down.” Villagers on the other side of the hill would see the sign and pass on the sign, so that anyone who saw it could hide in the caves.

Heo and Chun both expressed some misgivings about the film Jiseul. “They want you to know that this is fictional,” Yu related. “This is not exactly what happened, but this is just a part of the event.”

Jiseul, which means “potato” in Jeju dialect, is based on the true story of 120 Jeju villagers who lived in a cave for up to 60 days in an ultimately unsuccessful attempt to survive the massacre.

The film opens with a dense smoke that reveals scattered dishes on the floor of an empty home. This first scene reveals a consistent motif throughout the film — the obscurity of war contrasted with the homey strength of the Jeju people.

The portrayal of the villagers begins from an almost comical perspective with a scene of five men arguing over legroom, then proceeds to a teasing banter as the villagers attempt to find a cave in the snow. The black-and-white cinematography creates a sense of natural busyness as the villagers make their way through the messy forest.

| |

|

|

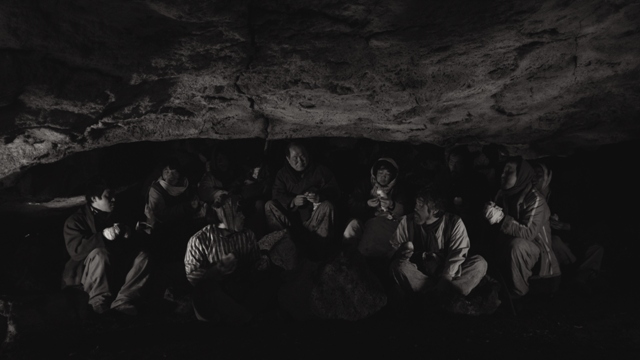

| ▲ Jiseul won the World Cinema Dramatic Grand Jury Prize at the 2013 Sundance Film Festival. Photo courtesy Japari Film |

This bustle is contrasted with the stark snowy fields and stone walls of the army barracks, where the bleak surroundings emphasize the unnatural anti-community of the barracks. This portrayal begins with a scene of the commander relieving himself, followed by his cold discussion around a young soldier who is made to stand naked in the snow.

Once in the cave, the villagers are visually isolated and their discussions become the only viewable reality. At first these conversations create their own warmth, as families lightly debate both the breeding of pigs and the marriage of sons. As the film progresses, however, the camera angle expands to include the surrounding darkness, then focuses in on individuals to create a sense of fear and isolation.

The film frames the American army as the responsible party in the minds of the Jeju people. “This gun is called ‘American Occupation,’ ” one villager jokes, as he handles a weapon while contrasting the present with the relative safety of the Japanese occupation.

Jiseul interacts with the imagined implication that Jeju people are simple through connecting them to the pigs stolen and slaughtered by the army. The film artfully carries this motif through to the conclusion that while the Jeju people may be seen as animals, it is the soldiers who choose to take on this identity.

Another strength of the film is the way in which it portrays both soldiers and villagers as individuals, and not simply as collective forces of good and evil. Some villagers argue to kill an army deserter, while others maintain that they have a duty to aid a person who is hurt. And while the commander of the army is shown as a clinically insane monster, another soldier wonders, “Do you really think there are rioters out there?”

One of the most poignant moments of the film occurs when a soldier stands over a disabled grandmother in the abandoned village, telling her he will burn her to death because of his hatred for all communists.

“What is a communist?” she asks. Her question is never answered.

While the film provides a window on the Jeju people at the time of the massacre, it does contain some problems. Due to the large number of characters and their shallow backgrounds, some of the storylines are difficult to follow, And, although ultimately poignant, the motif of potatoes comes across as slightly strained.

Unfortunately, the technology used to show the film at the December 20 screening also proved strained. Due to technical difficulties the film had to be stopped midway through the story, but not before it had sparked discussion amongst the audience, many of whom vowed to finish Jiseul via private showings.

“I thought Jeju was cold, now,” Alex Weatherhead remarked after seeing the bleak cinematography of the film. “We have it easy.”

Jiseul is a chilling glimpse into an era of Jeju’s history that is all but unimaginable today. Like the sticks placed on the hills by Heo and Chun’s families, this film raised the anguish of past generations into the tangible present of a December night at The Factory. From there, it is our own choice how we pass on Jeju’s stories. |