| |

|

|

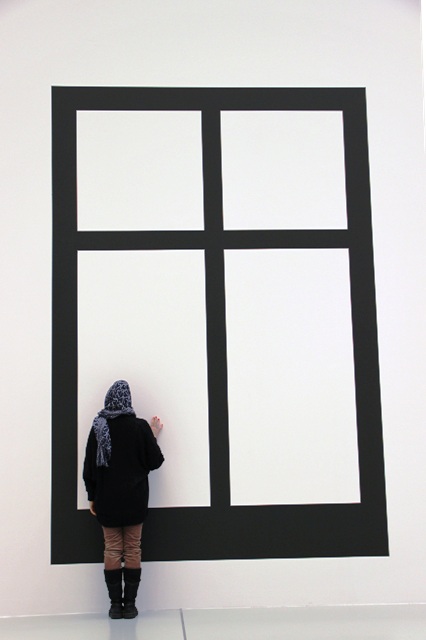

| ▲ How do we decide who is part of a culture? Kai Stachowiak |

In 2012 a young man visited his brother living and working in Korea.

During his stay, a skirmish in a small corner of his country erupted into a full blown war. He watched helplessly as the entire civil structure of his culture collapsed.

The situation rapidly disintegrated into carnage, violence laid waste to whole cities. The members of his family that had survived, fled.

These were not headlines about some distant foreign conflict, they were the loss of home and everything familiar. However, this young man was fortunate enough to have established himself in a culture that was itself, still working through the repercussions of a fratricidal war.

Millions of Koreans were once refugees in their own country, and the ongoing recovery from that period has created a profusion of intense challenges as well as diverse opportunities.

It’s part of the reason why he and his brother came here in the first place. And now, after 5 years, he speaks the language fluently, has a job, a car, health insurance, and the support of a thriving network of friends and associates.

Like many Syrians in Korea, however, he has a temporary visa - although his is better than most.

As of September 2015, the Ministry of Justice in South Korea said there were 848 Syrian asylum seekers in South Korea. Of those, only 3 have been accepted as refugees.

In 2016 the UN refugee office in Seoul told the New York Times that “war is not sufficient grounds for asylum”. Applicants must have suffered persecution.

It’s a strange distinction that the 1951 UN Refugee Convention supports.

War, famine, natural disasters, economic hardship and even slavery are not covered by the United Nations’ High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Fear of persecution is the core defining quality for being a refugee. Fleeing the effects of war isn’t.

This leads us to our second story. It’s about a woman born into a family that fought on the losing side of a different war.

For the survivors who weren’t put in jail, opportunities were few and suspicions were high. They were restricted from both business and education. Her mother did everything she could to keep the family solvent, but life was a constant struggle and the future, bleak.

As circumstances grew more desperate, the woman’s mother was faced with an incredibly difficult decision. In a daring gamble, she smuggled herself, her younger sister, and her two-year-old daughter onto a small boat.

The trip was only supposed to take three days, but they encountered a storm. A ship spotted them a week later, but didn’t pick them up. They gave the people on the boat food and water and pointed them towards a safe harbor. Legally, that’s all they could do.

| |

|

|

| ▲ Vietnamese refugees escaping in small boats Photo courtesy Tofs |

When they finally limped into port they were greeted with aid and temporary visas, but not a home. It would take three more years for them to find a place where they could emigrate permanently.

In the end they were given permission to resettle with former allies - a country that had opened its borders to those who had supported them during the war.

After a lot more work and preparation, they finally moved to their forever home.

The girl who had been the youngest person on that boat was now five and a half. She quickly learned the language as she absorbed the culture. She and her mother became citizens when she was 13.

She excelled at school and graduated from university. Going out into the world, she traveled and studied different languages. Eventually she found a job in Korea. It was here that she met a warm and affable Korean man whom she would eventually marry. They’re expecting their first child this spring.

The first half of her life was a progression from refugee to immigrant - fleeing persecution in order to take up permanent residence in another country.

She then graduated to expatriate, an ambiguous term that technically means living in a foreign country, but which has attracted connotations of being qualified, and taking advantage of job opportunities abroad.

There’s a certain amount of privilege in being called an expat, a title that speaks of choice - something rarely associated with refugees and immigrants.

Hers is one of the many success stories from the over 530,000 Vietnamese asylum seekers admitted to the U.S. from 1981 to 2000 - people who made the transition from dependence to autonomy.

The story of her achievements stands in stark contrast to contemporary trends in immigration.

Social and economic fears have been harnessed by populist movements around the globe, once again expressing otherwise well-founded concerns as a misdirected hostility towards inclusion.

This brings us to our last account about a man who left his country because of the violence, economic hardship and a growing intolerance.

There wasn’t a war - at least not like in the other stories. However, people were being killed with frightening regularity. And the poverty wasn’t abject, but he had lived in slums, struggling to keep food on the table.

With a lot of hard work he became the first man in his family to get a university degree. It took 8 years of mostly part-time study on top of holding down a patchwork quilt of menial jobs, but he did it.

Unfortunately, just as he graduated, a wave of prosperity crested and slowly began to recede. Jobs grew harder to find and wages stagnated. The country became entangled in yet another conflict; a new and alarming tide of aggressive nationalism began to surge.

Surrounded by growing disenfranchisement, caught in meaningless dead-end jobs, and struggling to stay healthy as his culture descended even further into substance abuse and suicide, he dreamt of escape.

All he had in the world when he arrived in Korea was an old suitcase, about 300 dollars, and a used one-way ticket. It was a rough start, but as the years progressed his life stabilized in important ways.

For the first time ever he had health insurance, dependable income, and a meaningful vocation. Eventually he met a lovely Korean woman, fell in love and they got married. A year later he and his wife achieved a dream he had given up on in his own country - they bought a house.

He had advantages in Korea that he had never known in his own culture. It was an important experience of abundance that helped him to better understand the many privileges that he had enjoyed in the United States without realizing it.

His gender, race, and nationality had given him enormous advantages (in both Korea and America) especially when you consider the trials and tribulations of his Syrian and Vietnamese-American friends.

He wasn’t a refugee, even though he had felt like one on occasion, but neither was he really an immigrant, or even an expatriate.

Like his friends he was now something in-between. They were all foreigners. It’s a status as full of potential as it is at uncomfortable and vulnerable - especially when popular sentiment is insular and phobic.

My Syrian friend surprised me when he told me that being called a refugee didn’t really bother him. However, being called a foreigner did. Being identified and treated as an outsider was a consistent and negative experience. But he also admitted that it would be much worse if his skin color were darker. Or if his gender were different. Or if he was religious.

It’s easy to lose touch with the nuance of individual stories amid the pomp of larger narratives, but you’d help someone in trouble, right? Someone who doesn’t have a country anymore? A two-year-old child lost at sea? A foreigner looking for a home?

Unfortunately the answers to these questions aren’t always easy or fair. Our humanity gets tangled up in economics, international politics, and cultural biases. Sometimes it feels safer to turn humans into refugees, immigrants, and expatriates; Koreans, Syrians, Vietnamese, and Americans into foreigners.

But we’re all still just people.

| |

|

|

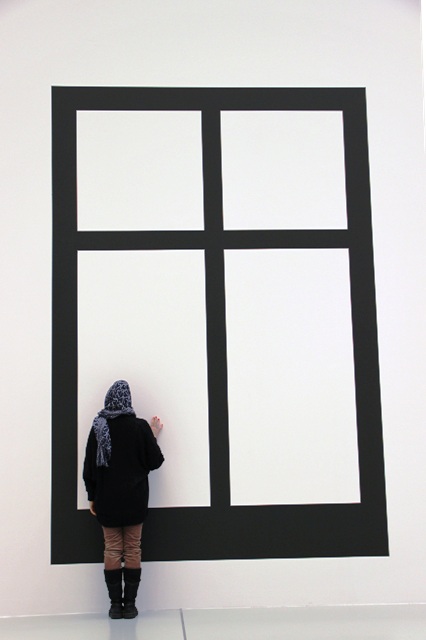

| ▲ At the walls the separate Photo courtesy Lachmann-Anke |

|