| |

|

|

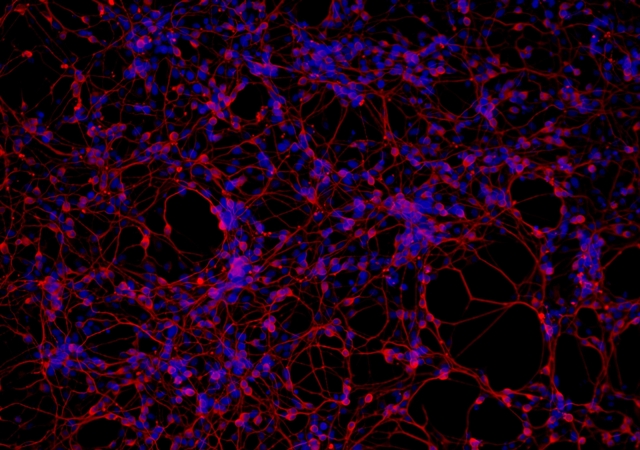

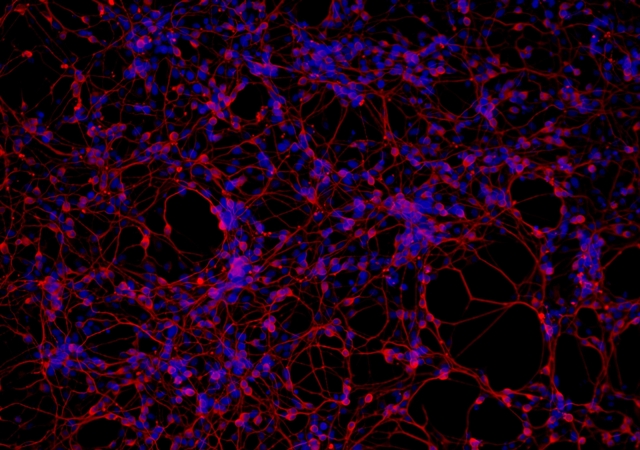

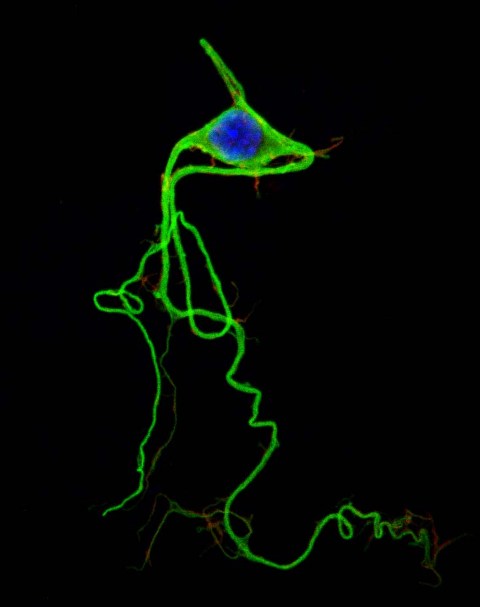

| ▲ Can you see yourself in here? Neurons stained red and nuclei stained blue Photo Courtesy Chempetitive |

At what point in your life did you decide some people are more attractive than others? Or is this sense somehow intuitive?

Disgust, for instance, is inborn. It’s part of our programming. A protective emotional response that evolved out of our sense of taste. Disgust shields us from foods that might harm us.

We have extended disgust, however, to cover much more than just bad food.

In everything from the size of certain body parts and the amount of hair you have, to cellulite and muscle tone, the human body is quite often considered disgusting these days. And this is not something we’re born with. It’s learned.

Your opinions about who is disgusting or attractive aren’t yours. They are your family’s, your peer’s, and your culture’s. Human images, multiplied on the surface of society, providing an illusion of depth. It’s a mesmerizing, albeit superficial reflection; variations on the myth of Narcissus writ large.

But this consensus reactivity is a cruel artifice.

Imagine, if you will, looking a child in the eye and telling them that they’re disgusting. Point blank, with a sneer. The majority of people wouldn’t do this, right?

But we have. We’ve all done this.

Children aren’t stupid. They know the secret language of scorn. The subtle ways in which we can be devalued with a gesture or a glance. We all know how it feels when a smartphone gets more attention than we do.

Or how about the patently transparent overvaluation that we lavish on others?

Who hasn’t witnessed the “halo effect” or the beauty bias? Where a physically attractive person is assumed to also be talented, intelligent, or successful, and treated differently because of it?

Our social economies elevate some by diminishing others. We all know these measurements intimately, but we rarely confront them in ourselves with any sustained self reflection. It’s just too damn scary.

However, consider for a second your feelings about how tall someone should be. Why do you care? Have you ever really thought about this? I mean really? Or why you have an opinion about how much someone should weigh?

What you have been taught to think is impacting who you want to vote for, your religious affiliations, your self esteem, and your relationships. Other people’s ideas about something as simple as appearance are shaping who you can or can’t love.

If you really pull on this thread, you’ll find that there’s a great deal about the world and yourself that’s based on opinions you’ve never really considered, never really struggled with in order to make them your own.

Parroting isn't the same as ownership. True ownership of what you know always comes at a high personal cost.

Moreover, when you really wrestle with your judgements, they tend to unravel. It’s like repeating a word so many times that it loses its meaning. You get to a point where you can’t suspend your disbelief any further and you just start seeing your opinions for what they are: reflections.

So why do we emulate the messages we receive throughout our lives, internalizing them as our own? Why do we believe that we are what the world tells us?

There are a dozen different, equally valid ways we could talk about this, but let’s start with a popular scientific angle.

Neurons are the Mirrors of the Soul

I’m sure you’ve read about them in the news, seen them on TV. Neurons are media darlings. Everybody’s got an opinion about them.

In much the same way that economists are being asked to comment on nearly every aspect of human life, neurologists are being interviewed these days on just about every topic imaginable.

Of course, the actual science is usually ignored in favor of easy to digest sound bites that make for juicy headlines: “Maximize Your Brainpower By Firing Every Neuron At Once”, as The Onion perfectly satirized.

This is a shame too, because the science here is Spock-level fascinating.

| |

|

|

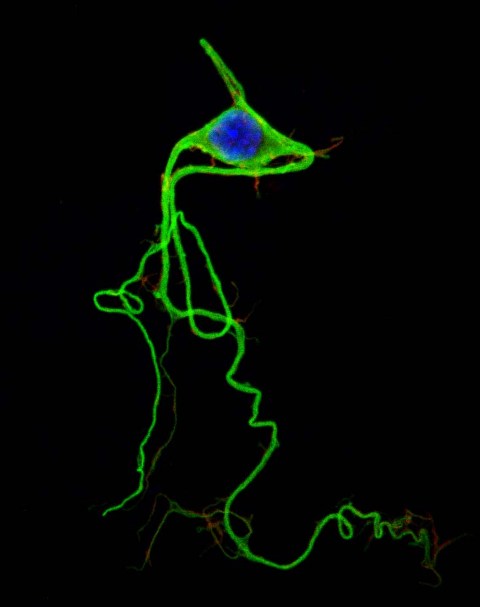

| ▲ A dyed neuron from a (Vulcan) chicken embryo Photo courtesy Xpanzion |

First positively identified way back in 1873 by Camillo Golgi, we are still finding different kinds of neurons, with over 200 types categorized so far.

They all send electricity (approximately 70 millivolts per neuron) as well as chemicals called neurotransmitters back and forth along a vast network throughout your body.

This network is called your nervous system, which, incidentally, is why neurons are also known as nerves.

The human body consists of an estimated 100 billion neurons, of which around 86 billion reside in your brain and 500 million sit in your so-called “second brain”, the digestive tract.

It’s worth noting that humans aren’t especially gifted, neurally speaking. Elephants have over 250 billion neurons in their brains, and long-finned pilot whales boast 37.2 billion neurons in their cerebral cortices - about 16 billion more than homo sapiens. And neurons might also be overrated since the humble sea sponge gets along in life without any at all.

But like I said, we love our neurons, and one type in particular has gained a great deal of attention in the last couple decades.

Discovered in macaque monkeys in 1992, and first directly recorded in humans in 2010, mirror neurons are a type of sensory neuron - they transmit information from your senses (like sight, sound, and smell) back to the brain.

Mirror neurons, however, have the unusual quality of firing not only when we are taking action - like touching an apple - they also fire when we see someone else doing the same.

This means that something deep within our makeup reflects the world around us. We are neurological copycats.

Neuroscientist V.S. Ramachandran has written that mirror neurons may be the cornerstone of empathy, imitation, learning, and language - possibly the very foundation of human culture itself.

Moreover, Ramachandran - one of Time magazine’s 100 most influential people of 2011 - has said that mirror neurons may represent the key to unlocking the mystery of human self awareness, which, if successful, would be the most significant scientific discovery ever made.

Then again maybe all this publicity is just a variation on the halo effect, attributing far more to a theory we find attractive than it really deserves.

It’s easy to get swept up in our stories - carried away in a torrent of compelling information, research, and the opinions of experts.

Did you find yourself getting wrapped up in the mirror neuron narrative? I sure was. It’s so much easier than doing all the work necessary to uncover the truth. Fact checking is bloody hard.

Imagine my surprise when I found out that the first study that identified mirror neurons in the human brain is also the only study to provide any direct evidence of mirror neural activity in the human brain.

One study. That’s it.

In “Single-Neuron Responses in Humans during Execution and Observation of Actions”, published in 2010 by Mukamel and associates, intracranial depth electrodes were implanted in 21 epilepsy patients. These electrodes recorded a small number of neurons that fired when an action was being taken as well as when it was being observed.

The rest of the 1,985 studies that show up in a PubMed search for mirror neurons rely on indirect methods, like functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scans or neuropsychological studies of brain lesions.

And some of these studies question the validity of current theories. Researchers at the University of Udine in Italy, for instance, have asked whether or not mirror neurons are even a distinct class of cells or if mirroring is a just function of neurons.

Does this mean theories about mirror neurons could be wrong? Of course it does, but that’s always the case with science.

Is this a hideous oversimplification of the science of neurons? Of course it is, but that’s always the case with writing.

I personally think neurology represents some of the finest research on the market today. However, I also think that mirror neurons are exciting and significant primarily because people love good stories and bad advertising.

We need everything to be part of grand narratives festooned with tawdry buzzwords and cheap hyperbole.

It’s Not You, it’s Us

We’re meaning making animals and we’re very lazy.

As Daniel Kahneman, winner of the 2002 Nobel prize in economics described in his best selling book “Thinking, Fast and Slow”, people depend on two basic systems of thinking.

System 2 is slow, conscious, energy intensive, and infrequently used. System 1 is used much more often because it relies on fast, easy, emotional, and stereotypical responses that are often driven by the subconscious.

We love fast thinking. It’s incredibly useful. Look! Spider! Kill!

| |

|

|

| ▲ Relax - this tiny spider doesn't have fangs large enough to pierce your skin Photo courtesy Pixabay |

We no longer face the same kind of challenges to our daily survival that we once did, and, unfortunately, our brains haven’t realized that yet.

Our brains have replaced actual threats with threatening concepts. As author Chris Mooney puts it, “we apply fight-or-flight reflexes not only to predators, but to data itself”.

This is as true for the scientists as it is for the scientifically challenged.

We run away from beliefs that scare us, holding tightly to initial impressions, mishandling the facts as we sprint forward, impatiently seeking conclusions that make us feel safe.

We tend to force our thinking to fit into what we know, rather than allowing anything that could potentially upset our delicate theories about the world.

Yet we need our fictions too.

Like science, imagination is one of our greatest tools in the exploration of reality. Where would we be without leaps of intuition? How many great achievements would have never been realized had it not been for the audacity of a belief in something that others simply dismissed as fantasy?

Is there anything we can do to keep these contradictory forces in check?

Maybe not.

In his TEDx talk, Tyler Cowen, nominated in 2011 by The Economist as one of the decade's most influential economists, said:

“...don't fall into the trap of thinking because you're agnostic on some things, that you're being fundamentally reasonable about your self-deception and your stories and your open-mindedness...not everything ties up into a neat bow, and you're really not on a journey here. You're here for some messy reason or reasons, and maybe you don't know what it is...”

So the bottom line is doubt and uncertainty scare us and the stories we create in order to feel safe mislead us.

This is usually the part of the article where some climactic observation is offered. A denouement in the third act that offers a satisfying resolution to all the conflict within the plot.

But the truth is, I don’t know what the truth is. No one does, and this is deeply vexing. And perhaps this isn’t a bad thing. Insight and resolution are important, but they’re not always what we need.

Maybe what we need is to lean into the messy unknown sometimes.

What Do You Mean?

How do I make space for experiences that are beyond my ability to contain? It’s one of life’s Great Questions.

We will all be beautiful and ugly at some point in our lives, fat and thin, smart and stupid, right and wrong, weak and strong, living and dead.

Life demands that we fill a multitude of roles and we simply can’t avoid all the unpleasant ones. Missing out on a fundamental experience of life is also a fundamental experience of life. You see what I mean?

Moreover we need our so-called negative experiences. They force us to develop tools to embody complications; a space with far more capacity for uncertainty than our ideas alone can provide.

Meaning-making is essential, but it has as much potential to buffer you from reality as it does of providing guidance. We tend to analyse everything at a distance, including ourselves, but I’m really very different when I’m existing than when I’m abstracting.

Meaning making and the brain are only small aspects of my total organism, and after years of focusing almost entirely on these facets I found that I had painted myself into a corner of sorts. I experienced a crisis of of inner homogeneity.

In response to this I had to seek a fulcrum point between the sense I make of the world and my senses. I had to learn that I have many more types of intelligence than I am consciously aware of - and I’m not waxing mystical here.

Take my body, for example. I have no idea of how to digest food, and yet my gut does it with stunning autonomy. Art has a similar feeling for me sometimes. It often seems to just does it all by itself.

Does this work? Does focusing on different senses give me an edge over obsessive thinking, fear, and negative experiences? Sometimes, but that’s not really the point. You're thinking too much again.

Just try to stay sensitive to those moments when you're not thinking and you’re just doing. Like Csikszentmihalyi’s (pronounced "Cheek-set-me-high") flow state.

Explore yourself. Find the places you always return to, and, in time, consider looking into the places that you avoid.

Start small, like how much you dislike certain types of music, and then move up the ladder. You may find that sadness, loneliness, depression, and illness have their own unique and necessary qualities that only reveal themselves when you get better at being present and tolerant.

Spend time in bothersome and even painful places. It won’t be easy, and there’s a lot that you can do to grow more skillful in your reflections, but please understand that none of this will allow you to transcend the challenges of this life. However it may help you embrace them.

Reinhold Niebuhr said man is his own most vexing problem. Gender specific pronouns notwithstanding, lock arms with this idea and work with it until, like a superficial understanding of beauty, you unravel the force of its meaning. Not until nothing is beautiful, but until you realize that beauty is all in your head.

Repeat the words and ideas that you live by. Repeat them over and over until they start to lose their cohesion. Get out of your mind once and awhile. Get to a point where you can’t suspend your disbelief any further and you just start seeing yourself for what you are.

| |

|

|

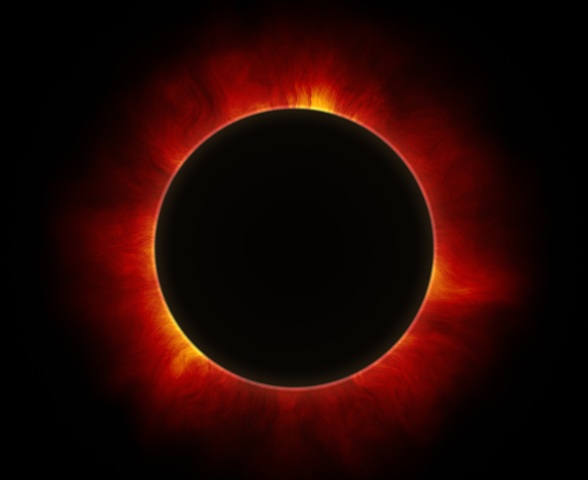

| ▲ Phenomena in a phenomenal world Photo courtesy Pete Linforth |

|