- Updated 2024.4.16 17:33

- All Articles

-

member

icon

-

facebook

cursor

-

twitter

cursor

|

LifestyleFood and Drink |

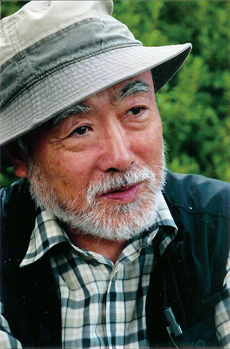

My dinner with Hyun Ki YoungJeju writer talks literature, the massacre, and his physical and mental torture |

|

I first learned of writer Hyun Ki Young a few years back while researching for The Weekly’s Jeju Massacre series. Hyun, a Jeju native, is credited with having written the first public mention of The Jeju Massacre (imprecisely known as 4.3 in Korean) with the 1978 short story “Sun-i Samch’on.”

For those who don’t know, the massacre was the result of an insecure, fragile country, enveloped in McCarthyism, trying to squelch dissenters on the island, then considered Communists, to the bifurcation of Korea. It was a horrific period from, officially, 1948 to 1954 with a death toll of an estimated 30,000 people, 80 percent killed at the hands of the government. In the following decades, talk of the massacre was tantamount to admitting to being a pinko, which was met with punishment. Hyun was not exempt from this and was unofficially arrested and tortured after the story’s publication.

Only since the year 2000 has discussion of the massacre truly been permitted.

I used the recent publication of an English edition of his story, “Sun-i Samch’on” (ISBN 978-89-94006-22-2), as an excuse to arrange an interview with the scribe to talk of literature and the massacre. We met at a small fish restaurant in Shin Jeju with Art Space C gallery owner and a friend of Hyun’s, Ahn Kye Kyoung, who acted as translator.

“Becoming a novelist means to acquire freedom. Literature is freedom,” said Hyun between sips of his beer. “But I have a complex in my mind … Why am I so complicated? Because of the 4.3 accident which I experienced [when I was] six or seven years old. That trauma insists on my mind. I want to be free. In order to be free I have to write about 4.3 to cure me of trauma.”

Fifty percent of his work, he said, is about the massacre. But even still, this is not enough to silence the guilt, and this freedom he seeks seems impossible for him to obtain.

“If I die and go to heaven I will meet 4.3 victims. I think they will torture me. Because at my age I neglected them. I didn’t write about them,” Hyun said in English.

“They will scold him, ‘Why didn’t you write well enough? You have to write better,’” Ahn added, for clarity.

“I am afraid of it,” Hyun said. “I want to write about 4.3 more, more beautifully.”

This is a challenge he claims he has no choice but to accept.

The story that he is best known for is essentially historical fiction, a combi-nation of the slaughter of 400 people in Bukchon village, and what Hyun experienced during the massacre in the Nohyeong area, his birthplace, and where we were eating one gargantuan fried fish head and drinking beer.

“Because it is history it wasn’t so difficult to write,” Hyun said, continuing that what was difficult was describing the behaviours of those who would have been much older than him during the massacre.

In many ways the book contains archetypal characters from the massacre, none more vivid than the narrator’s uncle, a former member of the North West Youth League (NWYL).

The NWYL were extreme right-wing militants who left the northern half of Korea when it was bequeathed to Kim Il Sung and his Soviet patrons. Angered about losing their homes, members of the NWYL, sent to Jeju by the newly formed South Korean government, were known to have been more cruel, more brutal than either the police or military to citizens they feared sympathized more with the North than the with the Seoul government and its attendent police.

“At that time young women have to get married to NWYL people in order to protect their family,” said Hyun. To this day, former members of the NWYL live, have families, and property on the island, acquired through these marriages during the massacre.

This has been one of the more troubling aspects following the massacre; having as neighbors those who murdered members of your family. Some committed these crimes for their own survival but, as Hyun pointed out during our conver-sation, some were committed from the evil that occasionally arrests men in positions of uncensored power.

“[Some] were forced to kill someone in the same community … forced by the armed soldiers or police, so they didn’t want to but they had to to survive. That was the moment to choose to survive or die, but among them there are people who were really, really bad and wanted to do that,” said Hyun.

His NWYL character is more the former than the latter, and for a very specific reason.

I told Hyun that during my research I read that he didn’t expect any fallout from the publication of his story. He said that, strictly speaking, that is not true. The good, former NWYL character was created with the hope that Hyun would be absolved in front of the Park Chung Hee dictatorship.

This was not to be the case.

After the publication of his story he attended a protest with a friend of his. They were both arrested.

“I was tortured for three days. I was tortured by the NIS [the Korean equiv-alent to the CIA],” said Hyun.

There were two men, one holding Hyun from behind while the other beat him, threatening him to not write about the massacre again. In the booth of the restaurant Hyun, slight in stature, demonstrated how he was restrained and mimicked taking blows to his ribs.

They made sure not to break his bones, he said.

“If bones were broken there would be problems.” Evidence that this unofficial arrest and torture occurred. Technically Hyun had committed no crime. If they arrested him there would have to be a trial, one that would expose to the rest of Korea the truth of the Jeju Massacre.

“My muscles swelled. The color was ink color, ink color all over my body. Bruise, you know? Ink color, ink.”

The government, almost 30 years after the massacre, was trying to silence any mention of the massacre.

“They didn’t want people to know about 4.3 … 4.3 is trouble and they wanted to keep 4.3 [quiet] forever.”

He is still writing about the Jeju Massacre, and the torture he experienced was reproduced in a book he is currently working on. Though the topic is consum-erism, and not about the massacre, it is difficult to picture anything this man writes to stray far from his self-appointed “mission,” ordered by those long passed.

“I was tortured because I was writing about this, but if you think of my death I will be tortured by the victims because I didn’t write about it enough.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ⓒ Jeju Weekly 2009 (http://www.jejuweekly.net)

All materials on this site are protected under the Korean Copyright Law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published without the prior consent of Jeju Weekly. |

|

|

|

|

| Jeju-Asia's No.1 for Cruise |

|

|

|

Title:The jeju Weekly(제주위클리) | Mail to editor@jejuweekly.net | Phone: +82-64-724-7776 Fax: +82-64-724-7796

#503, 36-1, Seogwang-ro, Jeju-si, Jeju-do, Korea, 63148

Registration Number: Jeju, Ah01158(제주,아01158) | Date of Registration: November 10,2022 | Publisher&Editor : Hee Tak Ko | Youth policy: Hee Tak Ko

Copyright ⓒ 2009 All materials on this site are protected under the Korean Copyright Law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published

without the prior consent of jeju weekly.com.

|